The current drought situation in the Horn of Africa is worryingly familiar, and according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the situation is deteriorating faster than expected. Severely erratic and below average rainfall has resulted in widespread food insecurity and malnutrition, deteriorating livestock conditions, and the mass movement of populations within and across borders.

Famine has officially been declared in South Sudan, compounding an already desperate situation that has led to the internal displacement of 1.9 million South Sudanese, and the cross-border displacement of more than 1.8 million more across the region. In Somalia, the latest figures indicate that nearly 700,000 people have been internally displaced since November 2016, while at least 2,000 Somalis have crossed into Kenya in recent months, and a further 4,000 have entered Ethiopia since the beginning of 2017, all in search of humanitarian assistance. In Eritrea, ravaging drought conditions are reported to be affecting half of the entire country, and reports from IOM and UNHCR suggest that more than 4,500 Eritrean refugees have crossed into Ethiopia since the beginning of 2017, with a reported 3,490 having crossed in March alone.

A new report published by the World Food Programme (WFP) concludes that food insecurity, along with income inequality, is a major ‘push’ factor driving international migration. While recent trends in the region appear to support the position that drought conditions have increased population movements, this article suggests that the impacts of the drought situation are limited to forced displacement within countries (internal displacement) and within the region only, with a completely opposite result on movements further afield, resulting in reduced migration along traditional migration routes out of the region.

Declining international migration movements

The potential effects of below average rainfall in the Horn of Africa first started to draw attention in late 2016. Forecasts by the Famine and Early Warning Network (FEWSNET) in November and December warned about deteriorating conditions, which began to correspond with shifting patterns of movement from the region.

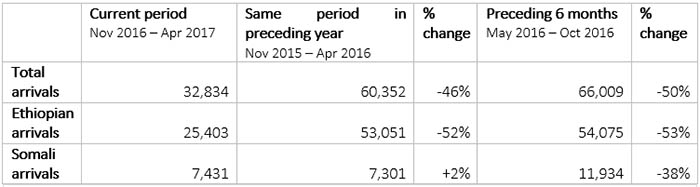

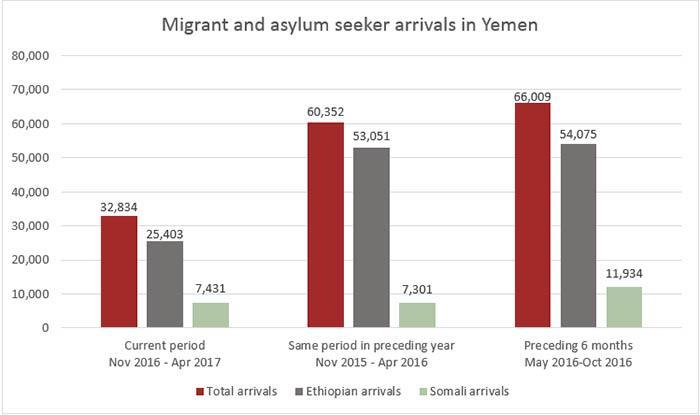

On the eastward route from the Horn of Africa towards Yemen, 32,834 Ethiopian and Somali migrants and asylum seekers arrived in Yemen between November 2016 and April 2017. 46% less than arrivals in the same period in the preceding year (November 2015 – April 2016), and 50% less than arrivals in the preceding 6 months (May 2016 – October 2016). The comparative decline in this period is especially remarkable given that 2016 was a record year for migrant arrivals in Yemen, and arrivals in the final quarter and first quarter of any given year are typically higher than other periods of the year.

Figure 1: Migrant and asylum seeker arrivals in Yemen

Source: UNHCR and RMMS

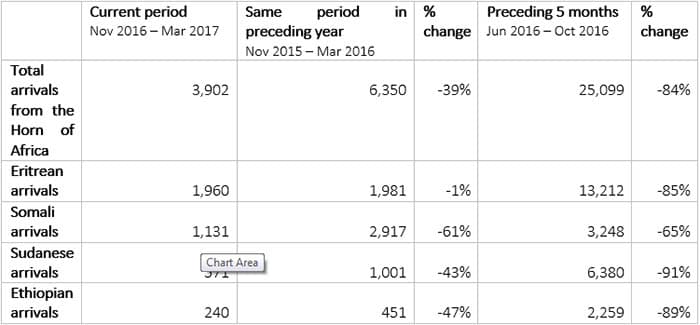

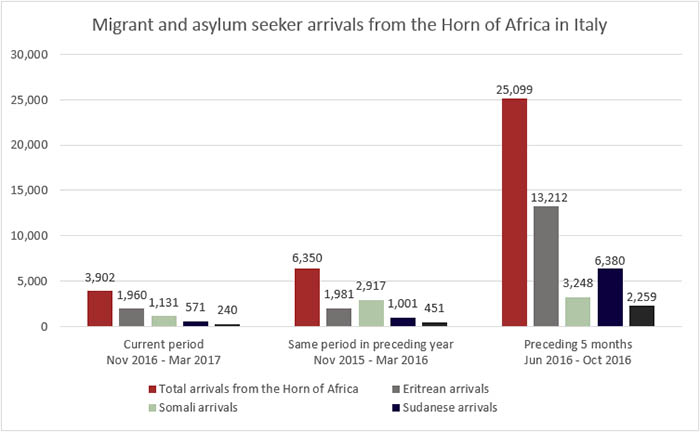

On the westward route from the Horn towards Europe a similar, but even more significant, reduction in movements was witnessed. A reported 3,908 migrants and asylum seekers from the Horn (Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan) arrived in Italy between November 2016 and March 2017. This represents a 39% reduction on arrivals in the same period in the preceding year (November 2015 – March 2016), and an 84% reduction on arrivals in the preceding 5 months (June 2016 – October 2016). While overall arrivals in Italy among Horn of Africa migrants reduced in 2016 when compared to 2015, this significant drop appears to indicate that something more may be at work. Overall arrivals (of all nationalities) in Italy are currently much higher than in previous years, with projections estimating that 250,000 will arrive in 2017, another record year after the previous record 181,436 who arrived in 2016, making the significant decline in arrivals from the Horn of Africa even more remarkable.

Figure 2: Migrant and asylum seeker arrivals from the Horn of Africa in Italy

Source: UNHCR and RMMS

Could drought be contributing to reduced international migration?

Several ideas have been put forward as reasons for the decline in movements out of the Horn of Africa in recent months. Deportations from Yemen and threats of deportation from Saudi Arabia are likely affecting movement from Ethiopia along the eastern route to Yemen and onwards to Saudi Arabia. The interception, detention and in some cases deportation of migrants in transit countries such as Sudan and Egypt are affecting movements towards Europe. It is possible however that impacts of the drought situation are also making a significant contribution in limiting international migration out of the region. Research by the University of Oxford’s International Migration Institute, shows that environmental stressors such as drought do not necessarily lead to migration, usually because migration, particularly long-distance and international migration, requires resources and during drought, resources are scarce.

According to the World Bank, how a household reacts to environmental hazards depends on the severity of the change they experience, their particular vulnerabilities, and available assets. In order to cope, families adopt a number of adaptive strategies including diversification of farming methods, non-farm work and using social support networks. For example in the current crisis, Somali diaspora networks are marshalling efforts on WhatsApp to raise money for their clans and sub-clans affected by the drought. However, when conditions deteriorate into prolonged chronic situations (such as drought), communities are forced to resort to “distress migration”, which by and large is internal and short-term. So far the data from the Horn appears to confirm this view, with much more internal displacement being registered than cross-border movement.

Depletion of assets

The prevailing drought in the region is in its third consecutive year, diminishing the capacity of communities to cope with additional shocks. Repeated cycles of climatic hazards, coupled with insufficient recovery periods, as has been witnessed in the Horn, reduce household and community coping mechanisms, and typically result in the adoption of harmful coping strategies that deplete household assets. Data from RMMS’s 4Mi project collected between November 2014 and April 2017 shows that migrants from the Horn of Africa (Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia) rely on a variety of sources to finance their migration journeys. However, more than half of the respondents interviewed (51% of 3,409 migrants) indicated that they relied on the disposal of assets (30% personal savings and 21% property sale) in order to migrate. A further 38% relied on loans from family and friends. In current conditions, it is likely that households have depleted resources that would otherwise have been reserved for migration, resulting in would-be migrants getting “stuck” in the region.

International migration does not come cheap. While journeys from the Horn of Africa to Italy can cost as much as USD 10,000, journeys between the Horn and Saudi Arabia (via Yemen) are considerably cheaper, ranging from USD 500-1,500. However, with drought conditions affecting asset bases for many of those on the move from Ethiopia (in case of the eastern route to Yemen often agro-pastoralists), funds that would have been typically reserved for migration for themselves or others are likely now being used to survive and help the community cope. 4Mi data shows that of 3,409 respondents, 76% did not have to pay for the entire journey prior to departure. Two-thirds (65%) reported that they were accessing funds along the way, often relying on financial help from both the diaspora and communities back home. Where migrants rely on financial support from communities at home, WFP suggests that migration itself can exacerbate food insecurity, resulting from the immediate lack of cash and long term impact of depleted savings and assets, or as family members incur debt.

A closer look at the profile of migrants may also reveal why outward migration is so affected. On the eastward route to Yemen, the reduction in arrival numbers on this route is much more pronounced among Ethiopian nationals than their Somali counterparts. The majority of migrants are Ethiopian nationals (83% in 2016), most of whom identify themselves as agro-pastoralists (farmers, cattle herders and shepherds) and travel to Yemen and Gulf States in search of economic opportunities. Agro-pastoralists are typically among the most vulnerable and most affected by climatic shocks, which result in poor harvests and depreciating value of livestock, leaving limited resources left to finance journeys. On the westward route towards Europe, 4Mi data shows a more diverse profile of migrants, with the most common being students, labourers, or unemployed. However, with most migrants having to rely on a disposal of assets or on money from family and networks to finance their journeys, it becomes more apparent why a decline in movement is also witnessed on this route.

Conclusion

Migrants and asylum seekers move for a number of different, and often overlapping reasons. Those moving from the Horn of Africa often communicate that they are moving as a result of poverty or limited livelihood opportunities in their countries of origin. The mass movement of populations currently being witnessed within the Horn of Africa can be directly linked to deteriorating drought conditions in the region, which have depleted asset bases normally reserved for times such as these. Households and communities have adopted adaptive coping mechanisms to deal with the effects of the drought, which for many (often as a last resort) is a decision to move. Research conducted by Oxford University, and others, conclusively shows that where migration is the decision, movement is often over short distances, over a short time, and mostly internal. Moreover, climatic shocks especially when chronic, reduce the likelihood of international migration, by reducing access to resources people need to migrate. A comparison of current movements in the Horn confirms this notion, e.g. Somalia where 700,000 are internally displaced while ‘only’ 6,000 have crossed the border into neighbouring countries, with even smaller numbers migrating further afield.

The data indicates that international migration movements out of the region have declined in recent months. Although further research is needed to establish more precise linkages between drought and food insecurity and short-distance displacement versus long distance international migration, this article suggests that the prevalence of drought, and its impacts on depleting household resources, has a negative effect on migration movement along typical migration routes out of the region.

Research commissioned by the European Commission identifies immobility amongst so called “trapped populations” to be an especially relevant policy issue. With projections that drought conditions across the region will worsen in coming months, and resources struggling to match the need, the vulnerability of populations unable to move, and thereby unable to generate income, will increase. We may expect to continue to see less international migration beyond the East African region, but more internal and cross-border displacement.

Note: This article originally appeared on the RMMS Horn of Africa website.